Interview with the French pianist Alexandre Kantorow, who is debuting this Season with Prokofiev’s Third Concerto.

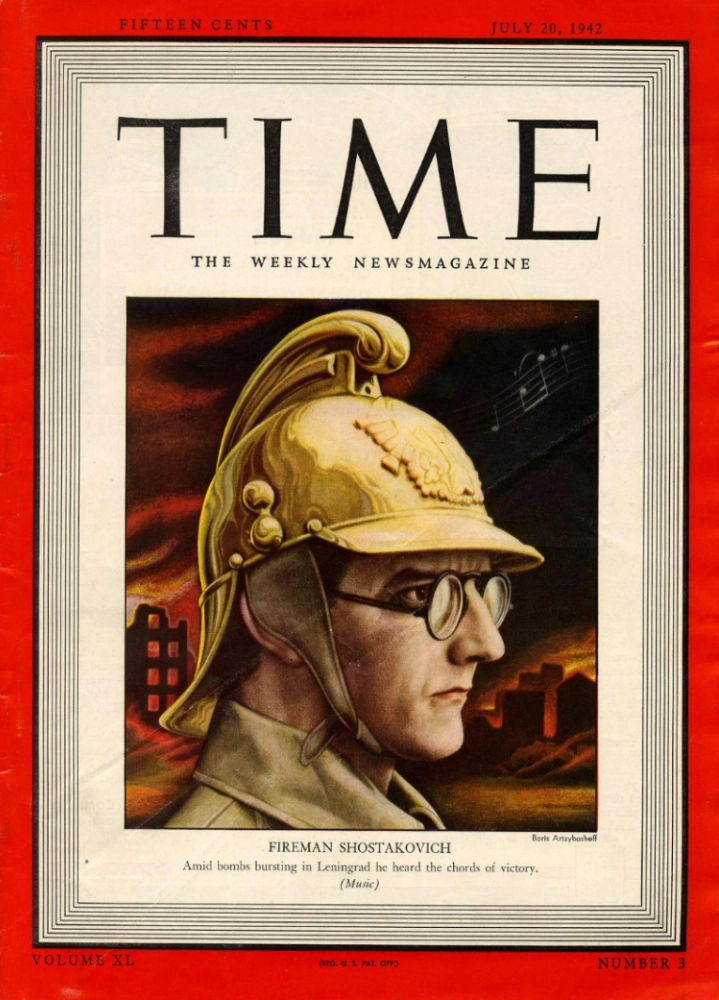

On June 22, 1941, Hitler launched the surprise attack against the Soviet Union. The rapid advance of the German tanks caught the Red Army unprepared, and within a few days the Wehrmacht reached the gates of Leningrad. The population reacted with extraordinary determination. Shostakovich repeatedly asked to enlist as a volunteer, but he was rejected and instead assigned to civil defense duties, including guarding the Conservatory. However, the most powerful means of resistance was his music. The Seventh Symphony, the “Leningrad,” was born quickly in the chaos of the first months of the siege and was described by Nikolas Slonimsky as a Blitzsymphonie, in response to the Nazi Blitzkrieg. Completed in December, it was first performed on March 5, 1942, in the same place, by the Bolshoi Theatre musicians conducted by Samuil Abramovich Samosud. The Symphony returns to Filarmonica’s music stands under the baton of Lorenzo Viotti. The essay by Franco Pulcini contained in the program notes raises some questions about the birth of this masterpiece. We decided to explore further with Irina Shostakovich, the ninety‑one‑year‑old third wife of the great composer. We received an email contact to which we wrote, with a mixture of excitement and skepticism, we in English and the AI in Russian, just to be sure. In less than an hour, Irina kindly agreed to give the interview in English.

The story of Irina seems to belong to a novel: born in Leningrad in 1934, the daughter of a linguist father, descended from a Polish‑Belarusian peasant family, and of a mother who was a teacher of Russian language and literature, she lost both parents at an early age: her father was arrested in 1937, and her mother died the following year. Raised by her grandparents and an aunt, she lived through the siege of Leningrad, facing hunger and deprivation, until she was evacuated across Lake Ladoga to Yaroslavl, where she also lost her grandparents. At only six years old, she managed to reach an aunt in Moscow thanks to a letter that miraculously arrived at its destination. After her studies, she worked at a music publishing house. There she met Dmitri Shostakovich: he needed approval for some corrections to a booklet, but that seemingly ordinary meeting marked the beginning of a bond that would, over the years, become companionship and love. Today, Irina Shostakovich is a witness to the life of one of the greatest composers and to a piece of twentieth‑century history.

The musicologist Franco Pulcini cites some historical sources according to which Symphony No. 7 had already been partly completed, and that the reference to the war with Hitler was simply a reassignment of hatred from Stalin to the German leader.

Shostakovich clearly stated, both to those around him and to others, that he wrote Symphony No. 7 in response to the events of 1941, namely the Nazi invasion of the USSR. In the symphony one clearly perceives the rejection of war; it expresses only a just and moral hatred.

The theme from Lehár’s The Merry Widow appears to have been conceived in the late 1930s, therefore before the German invasion, and only later acquired a meaning of heroic resistance.

Some music researchers do indeed find echoes of The Merry Widow in the invasion theme. However, there are no documents or arguments supporting the idea that this theme was developed long before the war. This conspiracy theory could be elaborated endlessly.

Hitler loved The Merry Widow. Was Shostakovich aware of this?

No, he was not.

An hour ago, I finished the score for two movements of a large symphonic composition. If I am able to complete it, I will call the work the Seventh Symphony. Why am I telling you this? I am telling you this to show that life in our city is normal. We are all at our battle stations. Soviet musicians, my countless comrades-in-arms, my friends! Remember, our art is in danger. Let us defend our music, let us work honestly and generously!

Dmitri Shostakovich, Leningrad Radio, 1942

The variation episode is often interpreted as a representation of the Nazi march toward Soviet cities. Does this programmatic and descriptive reading of the Seventh Symphony convince you?

The invasion theme is undoubtedly the theme of the Drang nach Osten.

What was Shostakovich’s true relationship with power, and how should it be understood in light of both the awards he received and the accusations he faced: was he submissive, aligned, mocking the regime, a victim, a dissident, or a partisan?

The relationship between an artist and power is never simple. Shostakovich always maintained honor and dignity. The entire world perceives the artist’s moral suffering in his music. No one has an easy life. He never lowered himself to ostentatious dissidence.

Shostakovich was many composers in one, capable of attuning himself to different sensibilities, shaping varied nuances, and working across a wide range of styles. Who was Shostakovich to you?

Shostakovich was and remains the dearest person to me, my faithful friend, and the very meaning of my life.

After the Lady Macbeth affair, he stopped writing operas. Did fate deprive us of a refined and modern opera composer, or was it a conscious choice?

After the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, Shostakovich began writing the opera The Gamblers in 1941, but did not complete it because of the length of Gogol’s novella. He wanted to use the entire text, but then it would have been as long as Parsifal.

To understand Shostakovich and his destiny, it is necessary to remember his supreme inner strength.

IIn an interview you said that he listened to Stravinsky with interest, admired Lutosławski’s Cello Concerto, and appreciated Benjamin Britten. Stravinsky always spoke harshly about Russian music. Was this interest mutual?

Stravinsky’s and Shostakovich’s interest in music, both Russian and foreign, especially in the works of recognized geniuses, never diminished. Shostakovich carefully kept a photograph of Igor Fyodorovich on his desk, under glass.

What would Shostakovich say today about the war in Ukraine? Once again Nazis at Russia’s gates to be fought, or regime propaganda?

Shostakovich was a great humanist, and his music confirms it.

Is it true that after choosing Toscanini for the long-awaited American premiere, he later regretted it because of a poor performance?

The performance of Symphony No. 7 conducted by Toscanini was not the American premiere. The symphony had already been performed in America and in other countries. A certain dissatisfaction Shostakovich felt toward Toscanini’s performance was probably due to the fact that he already had something with which to compare it.

What have we still not understood about Shostakovich, and what would help us understand him better?

To understand Shostakovich and his destiny, it is necessary to remember his supreme inner strength. To understand him better, one must listen more to his music, without allowing oneself to be distracted by various speculations.

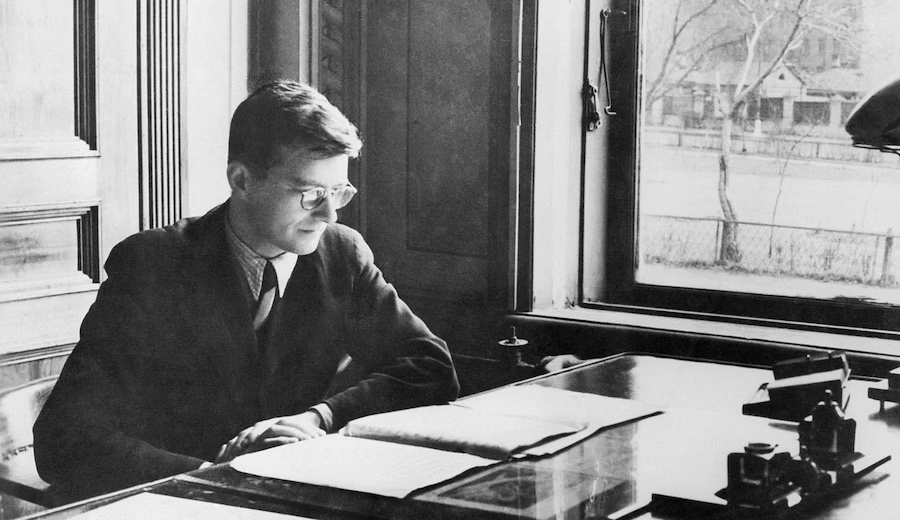

Despite efforts to locate the heirs of the authors of the photographs, they were unable to be located. The heirs of D.D. Shostakovich does not object to the publication of the composer's photographs in this edition.